Of all the corn varieties we've grown—and there have been hundreds—none have had such an interesting and secretive history as Minnesota 13. From almost the very beginning, questions have arisen about this variety's mysterious origin. Minnesota 13's co-creator, Andrew Boss, in 1894 listed the starting material for the line as simply "St. Paul" with the note above it "common" apparently implying that it was a common dent grown in the area around St. Paul, Minnesota. In subsequent reports on Minnesota 13 that included a "Materials and Methods" section, Boss always described the methods, but never the materials. Based on some work by longtime geneticist and corn historian Forrest Troyer, it is now believed that the line originated from a dent corn offered by DeCou & Co. also known as North Star Seed Co. of St. Paul, Minnesota.

Hays and Boss selected Minnesota 13 using the "centgener" breeding method which Hays pioneered. It was essentially an ear-to-row selection method whereby 100 seeds from each selected ear were planted in two-row plots. This marked the first use of a pure-line selection method, a notable advancement over selection methods of the day which favored bulking selected ears. The new method allowed for both retrospective selection (selecting the best ear from the previous harvest based on the combined yield of its progeny) and forward selection (selecting the best ears among the progeny). In later generations, the breeders also began detasseling undesirable plants within the test plots prior to pollination, a move that likely accelerated genetic gain.

Apart from the state-of-the-art method used, the most interesting detail, I think, about the selection method implemented by Hays and Boss is that it utilized a population of 12,400 plants per acre, notably higher than the plant densities of the day which typically ranged from 8,000 to 10,000. In 1899, row-thinning was overlooked altogether resulting in populations that were likely double the average of the time. These factors were important, I believe, because they pushed Minnesota 13's tolerance to plant density. Research published in 2005 by longtime Pioneer breeder Don Duvick showed that advancement in grain yields over the past hundred years are attributed mainly to increases in the number of plants per acre rather than yield per plant. It is possible, then, that Hays and Boss got a jump on this trend by increasing the density of their test plots.

Hays and Boss first began offering Minnesota 13 in 1900, albeit on a limited basis. Over the following years, they continued to improve the line using the centgener method. Minnesota 13's popularity sky-rocketed across the state as its early maturity and quick dry-down allowed farmers in the northern parts of the state the opportunity to grow corn for grain and not just fodder. Acreages of grain corn in Minnesota increased from 800,000 acres in 1893 to 2,200,000 in 1911 and Minnesota 13 soon became the most popular early corn in the northern United States, with acreages extending coast to coast and as far south as Arizona.

Hand pollination of corn to facilitate the breeding of improved varieties

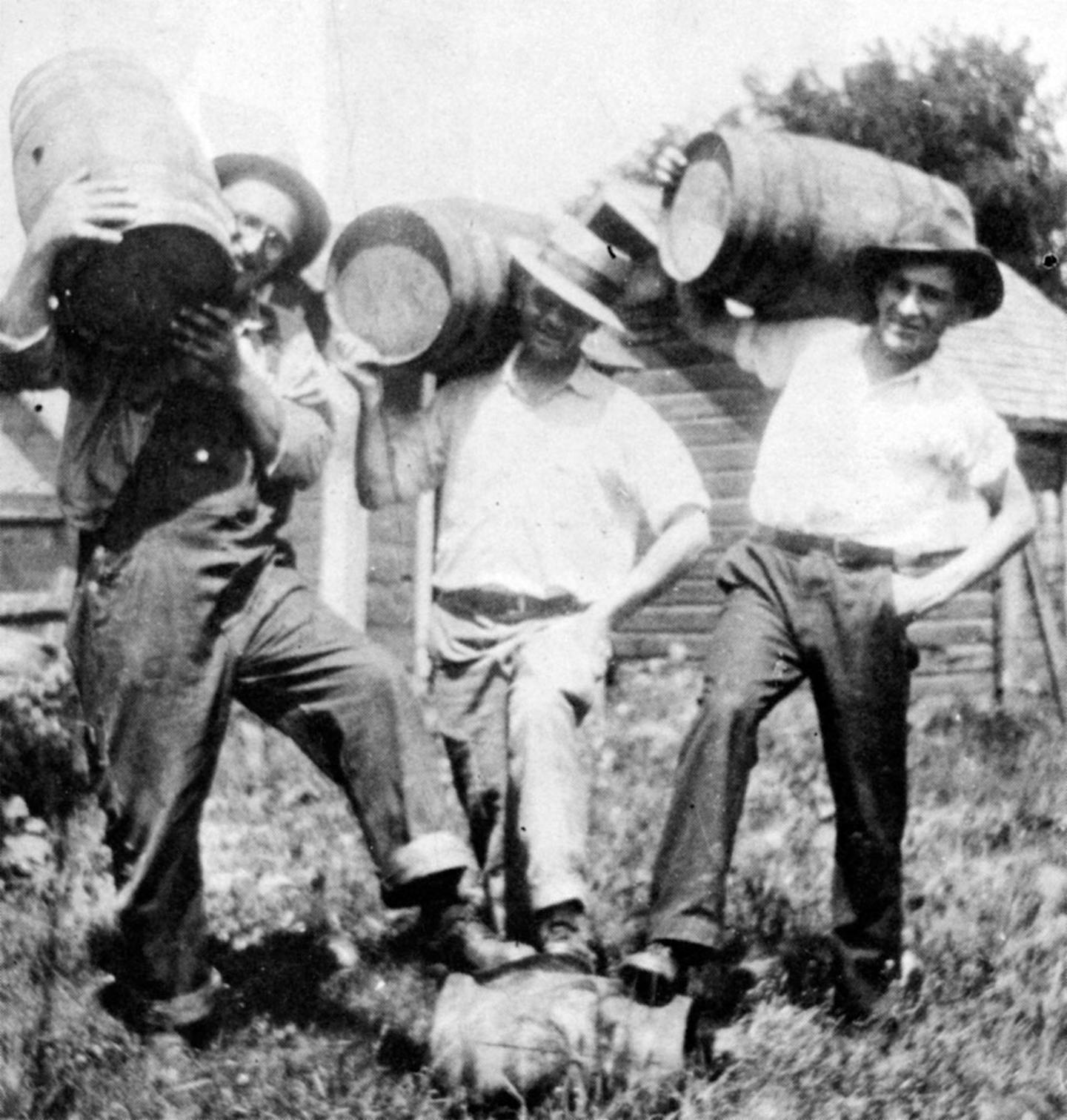

Despite its wild popularity with farmers throughout the early parts of the 20th century, most people had probably never heard of Minnesota 13. That is until the Prohibition Act, ratified in 1920, brought about the underground world of moonshining. Suddenly farmers throughout the US, struggling to make a living as the closure of distilleries and breweries reduced demand for their crops, were forced to take a look at the illicit trade.

One such group of farmers in Stearns County, Minnesota decided to take matters into their own hands. Aided by bought-off officials, cops running protection schemes, and even a sympathetic Catholic monk (you can't make this stuff up), the farmers turned their hardship into a successful enterprise. In barns and backwoods stills, the farmers developed a whiskey so good it could compete with trafficked Canadian brands. Possibly in homage to the corn that started it all, the whiskey carried a simple name, "Minnesota 13". In an era that produced a flood of harsh liquors that were poorly distilled, seldom aged, and sometimes cut with questionable ingredients, Minnesota 13 whiskey stood apart. Its flavor was exceptionally smooth and clean, qualities it gained through double distillation and proper aging.

Men hold up barrels of Minnesota 13 whiskey. Credit: Minnesota Historical Society

It is estimated that some 1,200 Stearns County farmers were involved in the making of Minnesota 13 whiskey at the height of Prohibition. Following the ratification of the 21st amendment in 1933, which repealed the Volstead Act, Minnesota 13 whiskey failed to make the transition to the legitimate marketplace. Some claim burdensome regulations made it difficult to compete, others assert that cultural preferences led German Catholics to return to their alcohol of choice, beer. Whatever the reason, Minnesota 13 remains an important chapter in Stearns County history, with locals disagreeing on whether the legacy is one of perseverance or shame.

Following the advent of hybrid corn, Minnesota 13 was used in the development of a number of inbreds, including dozens of public inbreds from at least five different states. It was also one of the main contributors in the development of Pioneer Hi-Bred's early commercial hybrids. Published estimates suggest that Minnesota 13 comprises nearly 13% of modern hybrids, probably due in large part to its role in the development of Pioneer's popular Iodent, PH207.

It's clear that Minnesota 13 played a very important role in helping corn breeders push yields to levels that were probably unimaginable at the time of its release. But with the dominance of hybrids today, does Minnesota 13 belong only in history books, like a black and white photo of some beloved forefather? In 2021, farmers and researchers from several universities initiated a project to compare the yields of test crosses made using a Dairyland open-pollinated (OP) line against other reportedly high yielding OPs and a couple of hybrid checks. Minnesota 13 was among the OPs tested.

The study, conducted across six states, concluded that most of the testcrosses and OPs were not competitive against the hybrids, unless taking into account their feed value, which is higher in OPs and synthetics. While the hybrids yielded an average of 191 and 205 bushels per acre respectively, the best test cross yielded only 157 bushels. The researchers concluded that to be considered for grain production at current input levels, an OP or synthetic would need to yield at least 90% of the hybrid to be competitive, and at these yield levels, the OPs were falling short.

| Pedigree | Type | Avg. Yield (bu/ac) | % Lodging | % Moisture | Yield/Moisture |

| FDO 8833 | Commercial Hybrid | 203 | 1.6 | 19.6 | 10.6 |

| FDO 8924 | Commercial Hybrid | 190 | 1.5 | 19.4 | 9.9 |

| Stan's OP | Open-Pollinated | 147 | 5.9 | 19.7 | 7.8 |

| Minnesota 13 | Open-Pollinated | 137 | 8.0 | 19.0 | 7.3 |

| Wapsie Valley | Open-Pollinated | 125 | 28.5 | 21.1 | 6.8 |

| Tommy Boy | Open-Pollinated | 125 | 14.1 | 21.6 | 6.2 |

| Dublin | Open-Pollinated | 118 | 23.6 | 22.6 | 5.6 |

| Dairyland | Open-Pollinated | 109 | 3.6 | 20.7 | 5.1 |

Kutka et al. 2021. Developing Affordable Seed Corn for On-Farm Production and Sales

Despite these disappointing results, one detail that surprised me is that the second highest yielding OP was Minnesota 13, a line that by most measures, has received little attention for nearly a hundred years. It notched a surprising 137 bushels per acre averaged across all locations, with its best yield coming in at 148 bushels per acre. Not bad for a line developed in an era where yields were typically less than 30 bushels an acre.

Anyone who has dabbled in plant breeding knows that it's a patient man's game. Advancements are made slowly and incrementally, facilitated by recombination. In other words, if you aren't growing out seed—allowing it to pollinate (and recombine)—and selecting, you aren't likely to see any improvement. Thus, it seems there might be an opportunity here. I'm left wondering, does Minnesota 13 have anything left in the tank?

The recent increase in input costs coupled with stagnant commodity prices have a lot of farmers thinking out of the box in terms of production systems. Today, it seems everything is on the table, from fertilization to seed. Might this bring about a new era for open-pollinated varieties like Minnesota 13? Honestly, who knows. It certainly wouldn't be the first time this mysterious corn has reinvented itself.

Interested in growing Minnesota 13 corn? You can find the seed here.

Leave a comment (all fields required)